Veiled Strength

Mother Right and the Rounwytha Tradition

Preface: On the Centrality of the Rounwytha Tradition

This essay takes the Rounwytha tradition as its point of departure. While Johann Jakob Bachofen’s Mutterrecht provides the conceptual framework for examining specific features of the tradition, the analysis that follows is not an exercise in classical reception or intellectual genealogy. Bachofen is employed here as a lens, not as an origin.

The Rounwytha occupies a distinctive position within the esoteric corpus of the Order of Nine Angles. Unlike more visible elements of the tradition—initiatory structures, aeonic speculation, or adversarial praxis—the Rounwytha represents a mode of knowing that is deliberately non-systematic, non-hierarchical, and local. Her authority is neither institutional nor doctrinal; it is experiential, inherited, and bound to place. As such, she resists many of the analytical categories typically applied to modern esoteric movements.

The purpose of this essay is to take the Rounwytha seriously on her own terms, without reducing her to metaphor, archetype, or ideological symbol. Rather than treating her as a “divine feminine” figure or as a vestigial mythological motif, I approach the Rounwytha as an epistemological figure—a bearer of a particular way of perceiving, interpreting, and inhabiting the world. This requires a comparative framework capable of articulating forms of knowledge that precede abstraction, codification, and formal doctrine.

Bachofen’s Mutterrecht offers such a framework, not because it provides a historical explanation for the Rounwytha, but because it describes a telluric, pre-juridical mode of consciousness whose structural features closely resemble those attributed to the Rounwytha tradition. The comparison is therefore functional rather than genealogical. It concerns patterns of knowing, authority, and temporality rather than lines of influence.

Throughout this essay, the Rounwytha remains central. Bachofen appears only insofar as his work clarifies what the Rounwytha is—and just as importantly, what she is not. The aim is neither to validate the tradition nor to dismantle it, but to render it intelligible as a coherent mode of knowledge that persists within a modern esoteric context.

I. Mother Right as a Mode of Knowing

Johann Jakob Bachofen’s Das Mutterrecht (1861) is one of the most frequently cited and least carefully read works in the history of religious and cultural theory. It is routinely reduced to a shorthand—“the theory of matriarchy”—that obscures both its method and its ambition. Read in this way, Bachofen becomes either a naïve evolutionist fantasising about female rule, or a proto-mythologist projecting romantic longings onto antiquity. Neither reading does justice to the text.

What Bachofen actually offers is neither a political theory nor a social blueprint, but an attempt to describe a primordial order of perception and meaning—a way of knowing the world that precedes written law, rational abstraction, and institutional religion. Mutterrecht is not primarily concerned with who governed whom, but with how early societies understood life, death, kinship, morality, and the sacred.

Bachofen himself was explicit on this point. His interest lay in the religious and juridical imagination of ancient cultures, not in reconstructing their administrative arrangements. As later translators and editors have repeatedly noted, Bachofen’s “mother right” refers less to rule in the political sense than to a cultural dominance of maternal principles in religion, ritual, and ethical life. Women appear in his work not as legislators or sovereigns, but as custodians of continuity, memory, and moral gravity.

This distinction is crucial. Bachofen’s maternal world is characterised by immediacy rather than mediation. Knowledge arises not from doctrine or revelation, but from proximity to natural processes—birth, growth, decay, death—and from the affective bonds that tie individuals to family, land, and ancestry. The mother, in this sense, is not merely a biological figure but an epistemic one: the bearer of a form of understanding rooted in care, empathy, and embodied experience.

In Mutterrecht, this epistemic order is consistently associated with the telluric. Earth, night, moisture, and cyclical rhythms dominate Bachofen’s descriptions of early religious consciousness. The maternal is lunar rather than solar, nocturnal rather than diurnal, receptive rather than directive. Time in this world is not linear or progressive; it unfolds in cycles, seasons, and returns. The dead remain present through memory and ritual; the living are bound to them through lineage rather than law.

Bachofen contrasts this order with the later emergence of what he describes as a solar–patriarchal regime, marked by abstraction, hierarchy, and the ascendancy of law over kinship. This transition is not presented as moral progress, but as a profound transformation in the structure of consciousness itself. The rise of paternal authority brings with it clarity, differentiation, and rationality, but at the cost of intimacy with the earth and with life’s cyclical nature.

Crucially, Bachofen does not romanticise the maternal world as harmonious or gentle. His maternal cultures are often severe, bound by necessity, and governed by inexorable natural law rather than mercy. Yet they possess a coherence rooted in belonging rather than command. Authority flows not from decree but from recognition: the mother knows because she has borne, cared for, and endured.

This point warrants emphasis, as it prevents Bachofen from being assimilated too easily into modern ideological frameworks. His maternal order is neither feminist nor anti-feminist in any contemporary sense. It does not advocate equality, liberation, or dominance. Instead, it describes a pre-juridical ethical field in which morality arises from relational bonds rather than universal norms.

For Bachofen, the maternal principle is therefore best understood as a mode of knowing and ordering reality. It privileges intuition over analysis, continuity over innovation, and empathy over abstraction. Symbols, myths, and rituals function not as allegories to be decoded, but as expressions of a lived relationship with the sacred. The divine, in this world, is not transcendent and distant, but immanent and enveloping.

This methodological orientation is what makes Bachofen unexpectedly relevant to certain strands of modern esoteric thought. When stripped of its speculative anthropology and nineteenth-century idiom, Mutterrecht offers a vocabulary for describing traditions that define knowledge as situated, embodied, and inherited, rather than revealed or systematised. It becomes less a theory of ancient matriarchies than a framework for recognising non-modern epistemologies that persist beneath or alongside dominant rational systems.

It is precisely at this level—epistemological rather than historical—that Bachofen becomes helpful in understanding the figure of the Rounwytha. The relevance lies not in claims about prehistoric societies, but in the structural features of a worldview that privileges earth-bound perception, aural transmission, and moral discernment over doctrine. Before the Rounwytha can be analysed on her own terms, it is necessary to recover Bachofen in this more restrained and precise sense: not as a mythologist of gender, but as a theorist of telluric knowledge and maternal authority as ways of knowing the world.

Only from this position does a meaningful comparison become possible.

II. The Rounwytha as a Bachofenian Survival-Template

If Bachofen’s Mutterrecht describes a telluric, pre-juridical order of knowing, then the Rounwytha tradition can be read as the localised persistence of such an order within a modern esoteric context. Crucially, this persistence is not framed as revival or reconstruction. The Rounwytha is not presented as a goddess-figure, an archetype, or a symbolic feminine principle, but as a mode of knowledge transmitted through inheritance, experience, and place.

The foundational text is explicit on this point. What is named “the Rounwytha tradition” is described not as a doctrine or system, but as an aural and experiential inheritance:

“What we call The Rounwytha Tradition is the muliebral essence that formed the basis of the aural, esoteric tradition I inherited from my Lady Master. It is a tradition which, it was claimed, was indigenous to the British Isles.” (Anton Long, The Rounwytha Tradition)

This opening statement already places the tradition outside the usual structures of modern occultism. Knowledge is inherited, not conferred through initiation; it is aural, not textual; and it is transmitted through personal proximity rather than institutional authority. In this sense, the Rounwytha occupies a position structurally analogous to the maternal figures Bachofen associates with early religious cultures: custodians of continuity rather than founders of systems.

The epistemological core of the tradition is defined with unusual clarity. The Rounwytha is not said to “believe” or “practice” in any conventional sense, but to cultivate a particular faculty of knowing:

“The basis of this tradition was the cultivation and use of what has often been described as the natural and hitherto (at least in most human beings, especially men) latent faculty of empathy. A faculty naturally possessed in abundance in the past in those few women whom the term Rounwytha describes and names.” (Anton Long, The Rounwytha Tradition)

This empathy is emphatically non-conceptual and non-discursive:

“Such natural, such Occult or esoteric, empathy is beyond words and terms – and forms the basis of all true ‘magick’, all genuine sorcery. For instance, the character of Rachael in the story Breaking The Silence Down is a fictionalised portrayal of a young Rounwytha developing her skills and using, for example, music to enchant, as a form of sorcery.” (Anton Long, The Rounwytha Tradition)

Here, the resonance with Bachofen becomes apparent. In Mutterrecht, maternal authority is grounded not in command or law but in an intimate attunement to life, death, and continuity. Knowledge arises from relation rather than abstraction. The Rounwytha’s empathy functions in precisely this way: as a pre-reflective sensitivity to beings, environments, and moral nuance, rather than as a symbolic or metaphysical principle.

The texts insist that this faculty is inseparable from locality. The Rounwytha is not a universal figure but a regional one, rooted in a specific landscape and cultural milieu:

“One of these European aural traditions was that of the Rounwytha tradition centred on the Welsh Marches and especially rural South Shropshire.”

This geographical anchoring is not incidental. It situates the Rounwytha firmly within what Bachofen would recognise as a telluric order, in which knowledge is shaped by land, season, and dwelling rather than by abstract cosmology. The Rounwytha knows from where she stands, not from a transcendent vantage point.

Equally important is the way authority is articulated. The Rounwytha does not rule, instruct, or legislate. Her authority is described in terms of muliebral qualities, a term the texts take pains to define carefully:

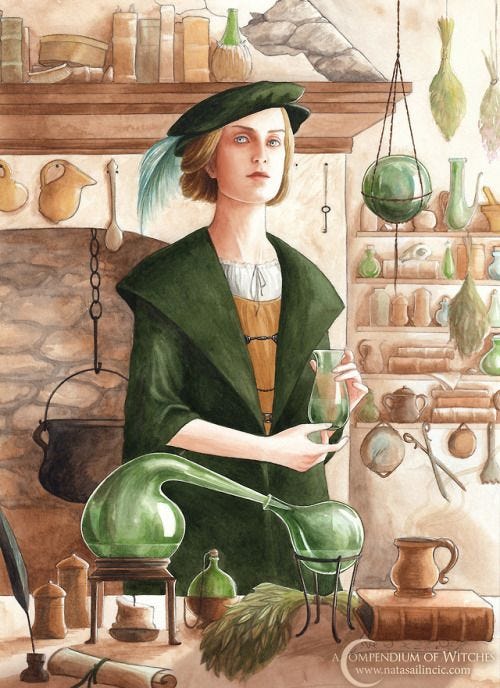

“Muliebral is the word we use, of Latin origin, to describe a particular type of lady, one of our kind – that is, the cultured, well-mannered, lady, possessed of esoteric empathy, who has acquired a particular wisdom through some years of experience both esoteric and exoteric. This is our archetypal Lady Master, also known as the Mistress of Earth. She who was once a Priestess but who has developed, matured, since then.” (Anton Long, The Rounwytha Tradition)

This wisdom is neither passive nor sentimental. Among the enumerated muliebral qualities are:

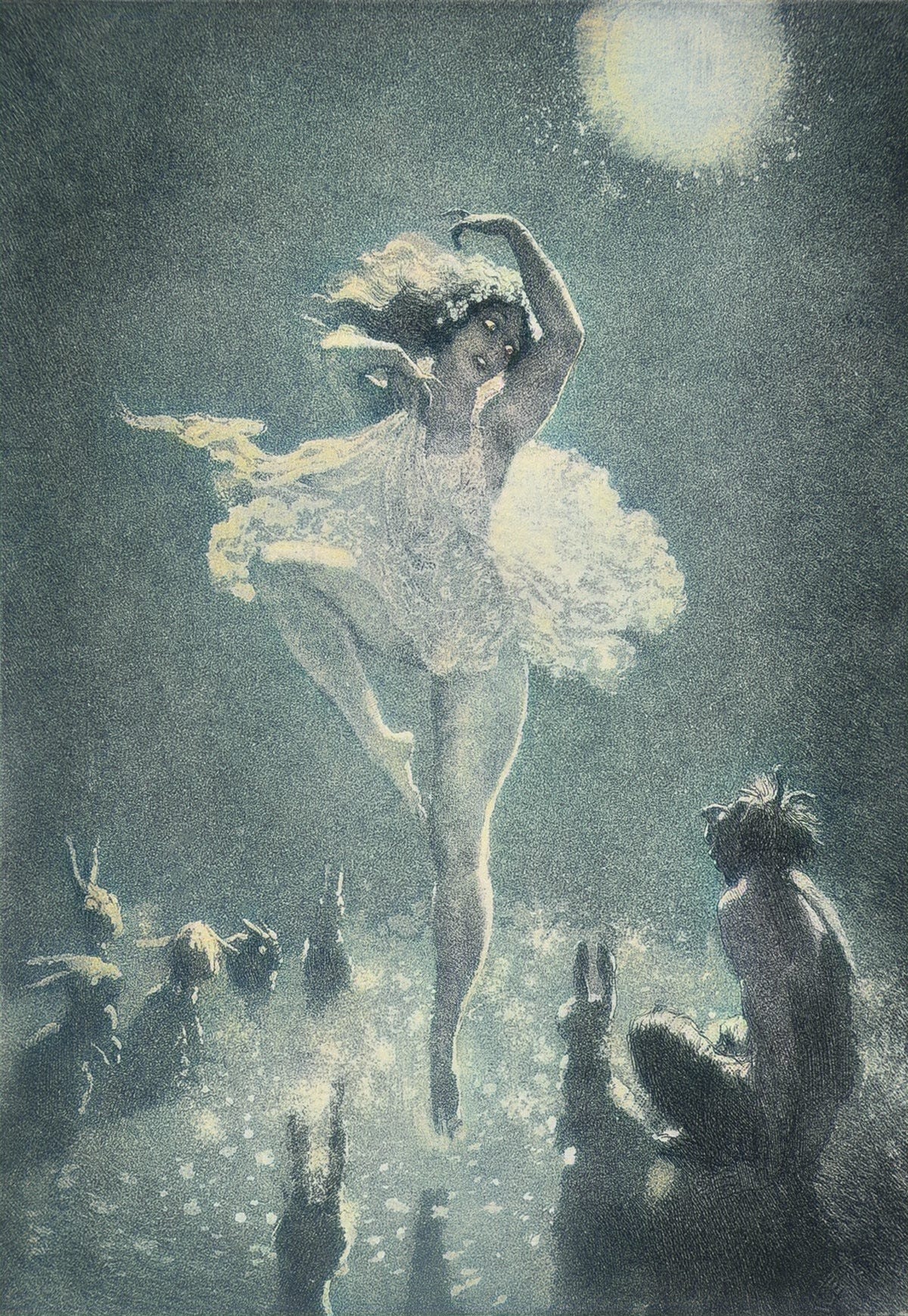

“Empathy; Intuition; Charm; Patience; Subtlety; and Veiled Strength.”

The phrase “veiled strength” is particularly telling. It echoes Bachofen’s insistence that maternal authority operates through moral gravity rather than coercion. The Rounwytha does not impose order; she maintains balance. Her influence is recognised, not enforced.

The tradition’s rejection of systematisation further reinforces this parallel. The Rounwytha way is explicitly contrasted with ceremonial magick, priestly structures, and doctrinal religion. The text warns against the dangers of abstraction and naming, arguing that older aural traditions understood the sacred as something that resists conceptual capture:

“There exists… an older aural tradition of how it is not correct – unwise – to give names to some-things.”

This resistance to naming recalls Bachofen’s method, in which myth and symbol are treated not as allegories to be decoded but as expressions of a lived relationship with the sacred. In both cases, meaning is not fixed by definition but emerges through practice, memory, and continuity.

Perhaps most revealing is the tradition’s emphasis on inheritance over initiation. The Rounwytha is not made; she emerges over time, through experience, and through relational embedding. The text repeatedly stresses that such knowing cannot be taught in the conventional sense:

“This empathy cannot be learned from books, or taught by words alone, but is developed through living and experiencing.”

This formulation places the Rounwytha squarely within a Bachofenian framework. In Mutterrecht, maternal cultures are characterised by precisely this form of transmission: knowledge is passed on through presence, care, and shared life, not through codified instruction. Authority rests with those who have lived longest within the cycle, not with those who articulate the most coherent system.

Taken together, these elements justify reading the Rounwytha as a survival template rather than a symbolic construction. She represents a demythologised, localised expression of a telluric epistemology that Bachofen identified in ancient cultures: a mode of knowing grounded in empathy, continuity, and earth-bound perception, persisting without priesthood, scripture, or universalising claims.

This does not require positing a historical lineage between Bachofen’s maternal cultures and the Rounwytha tradition. The comparison is structural, not genealogical. What matters is that both articulate a world in which knowledge precedes abstraction, authority precedes law, and meaning arises from dwelling within life rather than standing above it.

It is this structural affinity that allows the Rounwytha to be understood not as an eccentric addition to an esoteric system, but as its deepest and most archaic stratum—a residue of a way of knowing that modernity has never entirely erased.

III. Telluric Time, Empathy, and Muliebral Authority

The structural affinity between Bachofen’s Mother Right and the Rounwytha tradition becomes most apparent when attention shifts from questions of origin or symbolism to the underlying conditions of knowledge. Both articulate a world ordered not by abstraction, codification, or transcendence, but by telluric time, empathetic perception, and authority grounded in continuity rather than command.

Telluric Time and the Rejection of Abstraction

Bachofen’s maternal world is defined first and foremost by its relation to time. In Das Mutterrecht, Bachofen opposes earth-bound, cyclical temporality to the linear, solar temporality of later juridical systems. Maternal cultures do not measure time; they dwell within it. Time is experienced through season, growth, decay, and return rather than through abstraction or chronology.

Bachofen argues in Mother Right that maternal cultures remain oriented towards the natural course of becoming and passing away. The dead remain present through memory and ritual, and the living are bound to them through lineage rather than law. Time is not an external framework imposed upon life, but a flow lived through land, weather, and embodied continuity.

The Rounwytha tradition articulates a strikingly similar orientation. As Anton Long notes, those who possess esoteric empathy recognise that seasons are not fixed abstractions but processes discernible through changes in land, air, and living beings. Calendrical time is secondary to lived observation.

In both cases, abstraction is experienced not as enlightenment but as loss: the loss of intimacy with the earth and with life’s inherent rhythms. Telluric time resists systematisation precisely because it is lived rather than conceptualised.

Empathy as an Epistemic Faculty

If telluric time provides the temporal horizon of maternal knowing, empathy constitutes its primary epistemic faculty. In Mother Right, Bachofen consistently implies that maternal authority arises not from rational deliberation, abstraction, or codified law, but from affective proximity to life and death. Knowledge, in this register, precedes reflection. It is lived before it is conceptualised.

Bachofen’s sustained attention to burial rites, ancestral memory, and the ethical gravity of kinship reflects this orientation. Maternal cultures remain close to death, not as spectacle or transgression, but as continuity. The dead are not absent; they remain present through ritual, memory, and inherited obligation. Knowledge thus emerges not through speculative distance, but through endurance, care, and relational persistence.

This epistemic configuration is explicitly articulated in the Rounwytha tradition. Anton Long states in The Rounwytha Tradition that “the basis of this tradition was the cultivation and use of what has often been described as the natural and hitherto latent faculty of empathy.” This empathy is not framed as emotional sensitivity or ethical sentiment, but as a mode of direct perception. It apprehends relation rather than representation.

Crucially, Long insists that such empathy “is beyond words and terms – and forms the basis of all true ‘magick’, all genuine sorcery.” Empathy here is not communicable through doctrine or technique. It cannot be taught through abstraction. Like Bachofen’s maternal knowing, it is acquired through lived proximity to life’s rhythms rather than through instruction.

This shared insistence marks a fundamental epistemological divergence from systematised esotericism. Where systems seek articulation, codification, and transmissibility, empathetic knowing remains tacit, situational, and resistant to formalisation. It operates through recognition rather than explanation.

Muliebral Authority and Moral Gravity

The convergence between Bachofen’s maternal cultures and the Rounwytha tradition becomes most apparent in their shared conception of authority. In Mother Right, Bachofen repeatedly emphasises that maternal authority is neither coercive nor legislative. It does not command obedience through decree. Instead, it binds through moral gravity.

Maternal authority, for Bachofen, arises from continuity rather than sovereignty. It is recognised rather than enforced. Obligation in this world is not imposed externally, but inherited through kinship, memory, and shared endurance. Authority operates beneath formal structures, stabilising rather than directing.

This conception aligns precisely with the Rounwytha’s muliebral authority. Anton Long defines muliebral qualities as including empathy, intuition, charm, patience, subtlety, and “veiled strength.” The phrase is instructive. Strength is present, but concealed. Influence is exercised without display. Authority is effective precisely because it does not announce itself.

The Rounwytha neither initiates, commands, nor instructs. She discerns. She advises when asked. Her presence stabilises relations rather than reordering them. This authority is ethical rather than juridical, situational rather than universal. It mirrors Bachofen’s maternal principle not as power, but as gravity.

IV. Breaking the Silence Down as Phenomenological Fiction (revised, quote-integrated)

If the Rounwytha tradition articulates a telluric epistemology in doctrinal terms, Breaking the Silence Down renders that epistemology as lived experience rather than theory. The text does not explain the Rounwytha way; it inhabits it.

Anton Long is explicit about the text's position within the broader corpus. In the Introduction to Breaking the Silence Down, he distinguishes it sharply from the Deofel Quartet, writing:

“Unlike the works of the Quartet (which in the main are concerned with the polarity of male/female vis-à-vis personal development/understanding), this present work centres, for the most part, around the alternative, or gay (in this case, Sapphic), view.” (Anton Long, Breaking the Silence Down, Introduction, p. 8)

This framing signals a shift away from initiatory ordeal and confrontational praxis toward relational experience. The setting reinforces this. The narrative unfolds within a rural environment that is neither symbolic nor romanticised, but quietly determinative. Landscape shapes perception; space is not neutral.

The Rounwytha tradition likewise insists on locality: “One of these European aural traditions was that of the Rounwytha tradition centred on the Welsh Marches and especially rural South Shropshire.” (Anton Long, “The Rounwytha Way: Our Sinister Feminine Archetype,” in Baeldraca and Other Things Explained)

Within this setting, female–female relationships function as the primary medium of transmission. The sapphic intimacy depicted in the text is domestic, sustained, and quietly transformative. Desire operates as a bond, not a disruption; what matters is attunement.

Rachael’s own speech frames transformation as emergence rather than technique: “I don’t know. I feel different tonight. It was like I didn’t have to try. I can’t explain really. Once I’d begun, everything happened naturally. I’ve never felt like that before.” (Anton Long, Breaking the Silence Down, p. 72)

Her language repeatedly resists doctrinal explanation in favour of description and affect—consistent with the Rounwytha emphasis on empathy as a faculty that precedes abstraction.

When asked to play, Rachael makes the relational structure explicit: “I only play when I am inspired.” (Anton Long, Breaking the Silence Down, p. 72) and then: “You inspire me,” (Anton Long, Breaking the Silence Down, p. 72) The narration then refuses to reduce the effect of this music to symbol or instruction: “It was not Beethoven – it was Rachael and she, a joining of mutual souls. The music joined them together in an indefinable way.” (Anton Long, Breaking the Silence Down, p. 72)

That refusal of reduction echoes the Rounwytha insistence that such empathy is not adequately captured by words; in The Rounwytha Tradition, Long himself links esoteric empathy to “using, for example, music to enchant, as a form of sorcery.” (Anton Long, The Rounwytha Tradition)

Equally significant is the text’s refusal of explicit explanation. Long explicitly permits this non-exegetical mode of reading: “However, the MS can – like the works of the Quartet – be read without trying to unravel its esoteric meaning.” (Anton Long, Breaking the Silence Down, Introduction, p. 8)

This restraint mirrors the tradition’s suspicion of abstraction and naming. In Denotatum, Long notes “an older aural tradition of how it is not correct – unwise – to give names to some-things.” (Anton Long, “Denotatum – The Esoteric Problem With Names,” in Baeldraca and Other Things Explained)

Finally, moments of decision are framed affectively rather than ideologically. Rachael’s priorities are stated plainly: “I’m not ashamed to say that being here is more important to me than going to school or taking examinations.” (Anton Long, Breaking the Silence Down, p. 102)

In this way, Breaking the Silence Down completes the triadic structure established in this essay: Bachofen provides a theoretical description of a pre-juridical mode of knowing; the Rounwytha texts articulate its principles doctrinally; and the narrative renders that mode of knowing habitable as lived reality.

V. Against Archetype, Revival, and Ideology

At this point, it should be clear that neither the Rounwytha tradition nor its Bachofenian framing can be accommodated comfortably within the categories most often applied to feminine figures in modern esotericism. The Rounwytha is neither a goddess, an archetype, a priestess, nor a political symbol. To force her into any of these frames is not to interpret the tradition, but to replace it with something more familiar.

This is why the language of the “divine feminine,” so pervasive in contemporary occult discourse, is singularly inadequate here. That language presupposes symbolic elevation, mythic abstraction, and universalisation. The Rounwytha, by contrast, is resolutely non-mythic. She is local rather than cosmic, experiential rather than metaphorical, inherited rather than revived. Her authority does not derive from sacral office or metaphysical status, but from continuity, empathy, and place.

The same holds for Jungian archetypal readings. To describe the Rounwytha as an archetype is to abstract her from the very conditions that make her intelligible. Archetypes operate trans historically and psychologically; the Rounwytha operates situationally and relationally. She is not a figure of the collective unconscious but a bearer of a particular epistemic orientation — one that must be lived to be recognised. Reducing her to an archetype dissolves the telluric specificity that defines her.

Equally misleading are revivalist interpretations. The Rounwytha tradition does not present itself as a reconstruction of a lost pagan past, nor as a deliberate return to ancient goddess cults. It explicitly resists the logic of revival. Knowledge, in this tradition, is not recovered through historical reenactment or symbolic restoration, but preserved through continuity of practice and perception. What persists is not form, but orientation.

This point aligns closely with Bachofen’s own method. Mutterrecht does not advocate a return to maternal cultures, nor does it celebrate them as morally superior. Instead, it identifies a stratum of human consciousness that has been displaced but not eradicated. The maternal order, for Bachofen, survives not as an institution but as a residual mode of knowing, intermittently visible in myth, ritual, and social practice. The Rounwytha may be read in precisely this way: not as a survival of ancient society, but as a survival of telluric epistemology.

For this reason, political appropriations of the Rounwytha — whether feminist or anti-feminist — also miss the mark. The tradition neither argues for female dominance nor critiques male authority in ideological terms. Its conception of femininity is not oppositional but orthogonal. The Rounwytha does not stand in opposition to the Sevenfold Way or other initiatory structures as a corrective or alternative ideology; she exists alongside them as a different order of knowing altogether. Where one systematises, the other dwells. Where one abstracts, the other attends.

This distinction matters. Much confusion surrounding the Rounwytha arises from the assumption that all esoteric traditions aim at system, hierarchy, and ascent. The Rounwytha tradition does not. Its orientation is horizontal rather than vertical, cyclical rather than progressive. Authority does not accumulate; it settles. Knowledge does not expand; it deepens.

Seen in this light, the integration of Breaking the Silence Down into this analysis is not ancillary but essential. The text demonstrates what happens when such an epistemology is lived rather than theorised. It shows how knowledge circulates through intimacy, silence, and shared life without becoming doctrine. It also demonstrates how continuity can be sustained without mythic inflation, priesthood, or ideological framing. Fiction here does not embellish theory; it preserves its texture.

What emerges from this comparison, then, is not a claim about influence or lineage, but a recognition of structural affinity. Bachofen’s maternal order and the Rounwytha tradition describe the same fundamental orientation toward the world: one grounded in earth, empathy, and continuity, resistant to abstraction and law, and articulated through presence rather than proclamation. The former identified it as a foundational stratum of human culture; the latter embodies it as a lived esoteric practice.

To take the Rounwytha seriously is therefore not to mythologise her, but to resist the impulse to translate her into more palatable or familiar categories. She is not an answer to modern questions about gender, spirituality, or power. She is a reminder that other ways of knowing have existed — and continue to exist — alongside the systems that claim universality.

In this sense, the Rounwytha does not demand belief, allegiance, or revival. She demands attention. And it is precisely this demand — quiet, local, and resistant to abstraction — that makes her both difficult to interpret and impossible to dismiss.

Conclusion

The purpose of this essay has not been to establish a historical lineage between Johann Jakob Bachofen’s maternal cultures and the Rounwytha tradition, nor to argue for the empirical survival of a prehistoric social order. Instead, it has sought to demonstrate a structural convergence between two accounts of knowledge that operate outside the dominant frameworks of abstraction, juridical authority, and systematic doctrine.

Read carefully, Mutterrecht articulates a model of epistemic orientation grounded in earth-bound temporality, relational ethics, and pre-juridical authority. The Rounwytha tradition, as presented within the Order of Nine Angles corpus, exhibits the exact configuration of features: locality rather than universality, empathy rather than abstraction, continuity rather than innovation, and discernment rather than command. The comparison advanced here is therefore functional, not genealogical. It concerns modes of knowing rather than historical transmission.

The inclusion of Breaking the Silence Down further clarifies this point. As phenomenological fiction, the text does not illustrate doctrine; instead, it renders intelligible how such an epistemology operates when embodied. Its narrative economy—marked by silence, intimacy, and the absence of explicit instruction—closely aligns with Rounwytha’s resistance to systematisation and abstraction. In this sense, fiction becomes an appropriate medium for representing a mode of knowledge that resists conceptual closure.

Taken together, these materials suggest that the Rounwytha is best understood neither as an archetype nor as a revivalist figure, but as an epistemological configuration that remains legible within modern esoteric discourse precisely because it has not been fully absorbed by it. Bachofen’s work provides a vocabulary for recognising this configuration without reducing it to myth, psychology, or ideology.

The significance of this analysis lies not in resolving questions of origin or authenticity, but in clarifying the conceptual space occupied by the Rounwytha. She represents a mode of knowing that persists alongside, rather than in opposition to, systematised esoteric practice—a reminder that not all forms of esoteric knowledge seek articulation, hierarchy, or transcendence.

In this respect, the Rounwytha tradition functions less as an object of belief than as a limit case for esoteric analysis: a point at which explanatory frameworks reach their boundary and must give way to description. Recognising this boundary is not a failure of interpretation, but an acknowledgement of the epistemic diversity that esoteric traditions continue to contain.

Another excellent analysis - qv. https://sevenoxonians.wordpress.com/2025/12/20/the-rounwytha/

bro just keep cookin