Hermes Trismegistus Reloaded

David Myatt’s Corpus Hermeticum and the Making of a Pagan Semantic Field

Note to Reader

A brief note before we begin: this article inhabits a very niche intersection of my research—arguably one of the strangest corners where Hermetic studies and the study of the Order of Nine Angles overlap. It is, quite openly, a nerdy and highly specific deep dive, prompted in part by my reading of the captivating Western Paganism and Hermeticism: Myatt and the Renaissance of Western Culture, edited by Rachael Stirling, a text that raised enough discussion points to make this detour irresistible.

That said, this piece should not be taken as a sign of where my future work is heading. I needed to work through this material once—slowly, obsessively, and perhaps more granularly than any reasonable reader would expect. Upcoming essays will be broader, more accessible, and far less dependent on one’s willingness to parse Greek vocabulary or trace the ideological afterlives of fringe esoteric groups.

So, if what follows feels like a deep dive into a deep dive, that’s intentional. Consider it a one-off excursion into a peculiar terrain before we return to calmer, more satanist-friendly ground.

Introduction: David Myatt and the Problem of Hermetic Translation

David Myatt’s translation of the Poemandres—the first treatise of the Corpus Hermeticum—presents itself not merely as a linguistic exercise but as a hermeneutic intervention in the long and contested history of Hermetic interpretation. Where most modern translators approach the text as a product of late-antique philosophical religion, Myatt reconstructs it as a window into what he describes as an archaic, pre-Christian “weltanschauung,” one whose conceptual vocabulary must be preserved from the interpretive overlays of subsequent centuries.¹ This stance becomes evident from the very first lines. The Greek describes an overwhelming manifestation of φῶς (phos), traditionally rendered as “light,” followed by the appearance of a boundless being offering revelation.² Myatt deliberately refuses the conventional translation, retaining phos in transliteration and amplifying the visionary strangeness: “an indefinity of inner sight,” he writes, where everything is “suffused in φῶς (phos), bright and clear,” before the scene ruptures into “heavy darkness—στυγνόν, strange—slithering as a serpent.”³ In doing so, he positions translation itself as a means of cultural reclamation. As Rachael and Richard Stirling argue in their piece in Western Paganism, Myatt’s work restores the pagan ethos of balance, harmony, elegance, and rectitude, which Christianity supplanted,⁴ thereby transforming the act of translation into a form of ideological recovery. This article examines that claim from an etic perspective, treating Myatt’s translation not as a neutral philological artefact but as a deliberate rewriting of the Hermetic tradition and a significant moment in the modern reception of ancient esoteric texts.

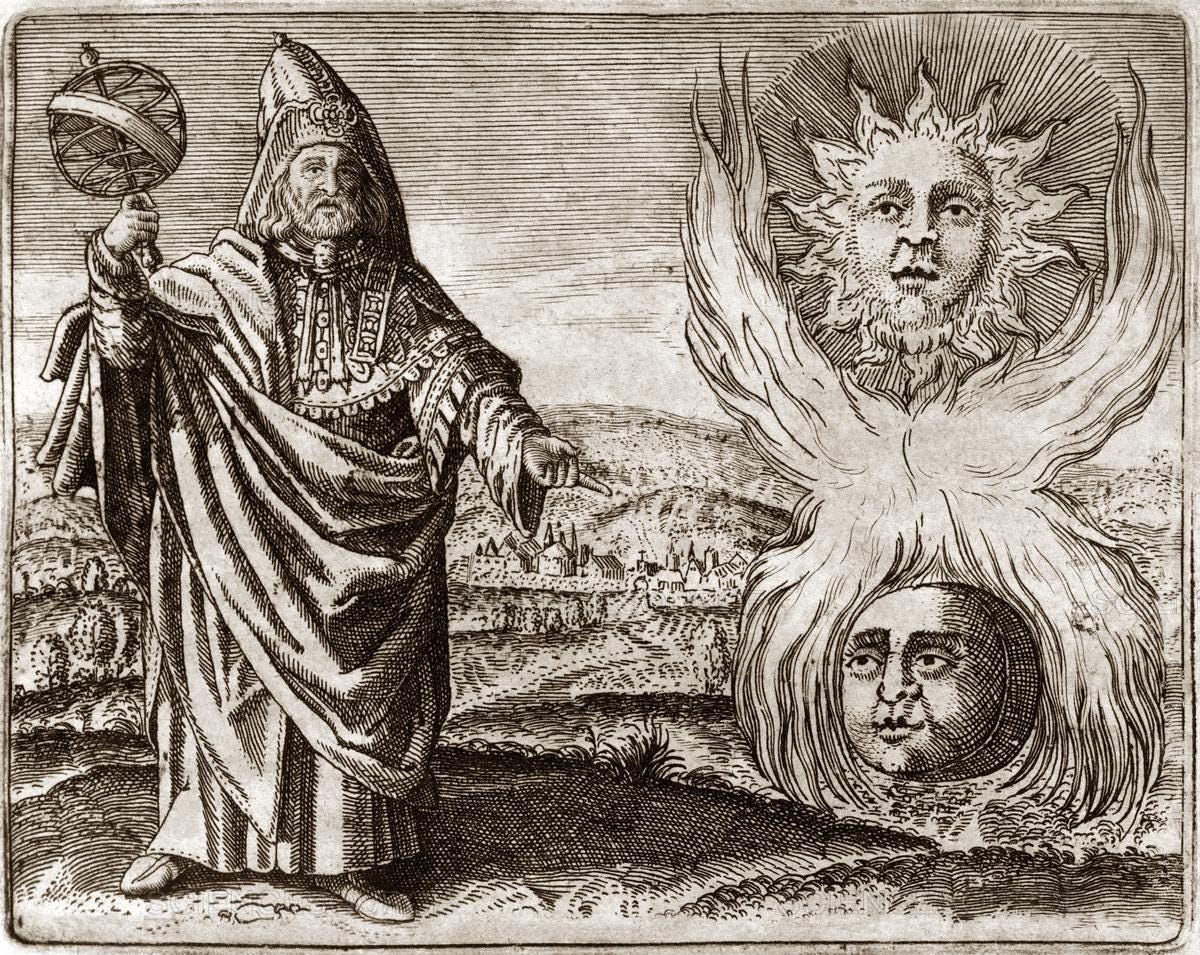

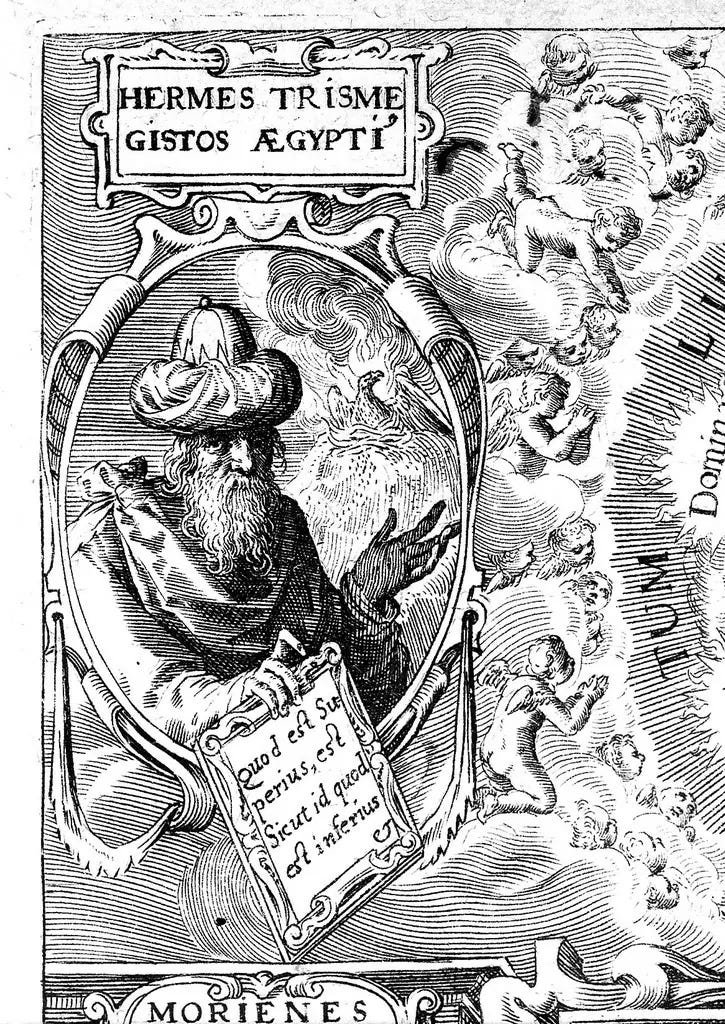

Myatt’s translation appears at a moment when the Corpus Hermeticum has already been subjected to several major interpretive regimes, each imposing its own conceptual architecture on a heterogeneous body of late-antique texts. Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), working within the intellectual currents of Florentine Platonism, rendered Hermes Trismegistus a proto-Christian sage whose teachings anticipated the Incarnation.⁵ Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century translators such as G.R.S. Mead (1863–1933) reframed the Hermetica within Theosophical universalism, while modern scholarship—exemplified by A.D. Nock (1902–1963), André-Jean Festugière (1898–1982), and Brian Copenhaver—has emphasized the syncretic, Egyptian–Greek, and philosophically eclectic milieu of Roman Egypt in the second and third centuries CE.⁶ Myatt positions himself against this entire lineage. His stated aim is not to clarify the text’s historical complexity but to strip away what he calls “retrospective reinterpretation” and thereby allow a distinctively “pagan” cosmology to re-emerge.⁷ Stirling et al.’s reading develops this further, asserting that Myatt’s lexical and stylistic choices reveal an underlying Western pagan ethos that both Christian theological frameworks and secular academic approaches have systematically obscured.⁸ Whether such a reclamation can be sustained philologically or historically is a separate question. The present study approaches Myatt’s translation not as the recovery of an authentic cultural substratum—a claim that would require emic assent—but as a strategic reconfiguration of a multivalent tradition, one that selectively reorganises the Hermetic material to articulate a coherent, singular, and explicitly non-Christian philosophical identity.

The methodological concern that guides this article is therefore twofold. First, it examines Myatt’s translation as a semantic and conceptual reconstruction—a deliberate reshaping of the Hermetic lexicon through neologism, selective transliteration, and the amplification of archaic imagery. Second, it analyses the authors’ parallel claim in Western Paganism that this reconstruction effectively discloses an underlying “Western paganism,” treating their position not as an emic insight into the Hermetica but as an ideological reading that warrants contextualization within modern debates on tradition, identity, and the uses of antiquity.⁹ Against this framing, the article draws on the work of scholars such as Garth Fowden, Roelof van den Broek, and Brian Copenhaver, whose analyses of the Hermetica emphasise the hybridity, syncretism, and intercultural entanglement characteristic of Roman Egypt, rather than any putatively coherent pagan substratum.¹⁰ The central question is not whether Myatt accurately reproduces the “original worldview” of the Hermetica—a question rendered untenable by the composite, anonymous, and heterogeneous nature of the texts—but rather what his translation does, ideologically and hermeneutically, within the contemporary landscape of Western esotericism. By exploring Myatt’s lexical choices, the interpretative claims of Rachael Stirling and the other authors of Western Paganism, and the modern scholarly consensus on Hermetic syncretism, this study treats translation as a form of cultural production that both reflects and constructs philosophical identities. The sections that follow therefore analyse Myatt’s semantic system in detail, situate it within the longue durée of Hermetic reception, and assess its implications for the ongoing contest over the meaning and ownership of the Hermetic tradition.

The Hermetic Lexicon

Any attempt to understand Myatt’s translation strategy must begin with the fundamental instability of the Hermetic lexicon itself. The Greek terminology employed in the Corpus Hermeticum—terms such as νοῦς (nous), λόγος (logos), φύσις (physis), ψυχή (psychē), and πνεῦμα (pneuma)—entered the Roman imperial period already burdened with centuries of philosophical, religious, and technical usage. Plato (427–347 BCE) had treated nous as the highest faculty of intellectual apprehension, the site of direct knowledge of the Forms.¹¹ The Stoics reconfigured logos as the rational structure immanent within the cosmos, while Middle Platonists such as Numenius (2nd century CE) employed nous and logos in complex triadic metaphysical systems.¹² Early Christian authors, especially in the Gospel of John and the Pauline epistles, adopted both terms with new theological emphases.¹³ By the time the anonymous authors of the Hermetic tractates composed their dialogues in the second and third centuries CE, none of these words could be used without evoking a web of competing associations. This semantic density is reflected in the manuscript tradition of the Hermetica itself, where divergent vocabularies—philosophical, cosmological, ritual, and theurgical—appear side by side.¹⁴ As A.D. Nock and A.-J. Festugière demonstrated in their critical edition, the Hermetic authors neither adhered strictly to one philosophical school nor articulated a stable conceptual system; instead, they appropriated familiar Hellenistic terms into a discourse that combines Platonic metaphysics, Stoic cosmology, Egyptian temple theology, and what van den Broek calls a “distinctively revelatory mode of teaching.”¹⁵ In this context, translation is never a neutral relay of meaning but an interpretive act that navigates—and inevitably prioritises—certain historical trajectories of usage over others. Myatt’s translation distinguishes itself precisely by resisting the dominant trajectories anchored in Christian, Neoplatonic, or scholarly rationalising frameworks, foregrounding instead the vocabulary's strangeness, instability, and pre-Christian resonance.

The translation history of the Corpus Hermeticum reveals how successive interpreters stabilised this unstable lexicon by aligning it with the dominant intellectual frameworks of their respective eras. Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), translating the Hermetica into Latin in 1463 at the behest of Cosimo de’ Medici, mapped the key Greek terms onto the conceptual architecture of Christianized Platonism.¹⁶ Thus νοῦς (nous) became mens, the divine mind accessible to the purified soul; λόγος (logos) became verbum, the creative Word echoing the Johannine prologue; and φύσις (physis) was rendered as natura, the hierarchical order of creation. Ficino’s translation effectively naturalised the Hermetica within the prisca theologia, the primordial wisdom tradition that he believed anticipated Christian revelation.¹⁷ By contrast, G.R.S. Mead (1863–1933), working within the esoteric and Theosophical milieu of the early twentieth century, inclined toward a universalist reading that softened conceptual tensions by appealing to perennial metaphysics; his English tends toward abstraction, subsuming lexical differences under the rubric of a unified “wisdom-religion.”¹⁸ Modern academic translators—including Nock, Festugière, and Copenhaver—sought to correct these theological or syncretic harmonizations by attending more closely to philological nuance and the cultural complexity of Roman Egypt. Nock and Festugière emphasized the composite layering and “opportunistic eclecticism” of the texts, while Copenhaver’s 1992 translation rendered νοῦς, λόγος, and φύσις in a consistent, philosophically neutral vocabulary intended to avoid theological overtones.¹⁹ Yet as scholars such as van den Broek and Jean-Pierre Mahé have noted, even this academic clarity introduces a form of homogenization, tending to systematise what the Hermetic authors themselves left intentionally fluid.²⁰ It is precisely these stabilizing tendencies—whether Christianizing, universalizing, or rationalizing—that Myatt’s translation seeks to counteract, not by offering a philological correction, but by constructing an alternative semantic field grounded in a self-consciously pre-Christian sensibility.

Myatt’s Retrospective Reinterpretation

David Myatt positions his translation explicitly as a corrective to what he terms “retrospective reinterpretation,” a process by which later intellectual frameworks—especially Christian theology, Neoplatonic metaphysics, and modern rationalism—have imposed coherence or doctrinal consistency on texts that were neither systematic nor exclusively Greek in origin.²¹ His approach involves two principal strategies: first, the deliberate retention or transliteration of key Greek terms (φῶς, νοῦς, λόγος, φύσις) to prevent their assimilation into familiar conceptual categories; and second, the selective creation of English neologisms—most notably “perceiveration” for nous—intended to evoke what he claims to be an archaic experiential modality unavailable within post-Christian conceptual vocabularies.²² The stated aim is not philological precision in the conventional sense but the reconstruction of a pre-Christian semantic horizon, one presumed to have animated the Hermetic authors but subsequently obscured. This program is echoed and amplified by Western Paganism, which argues that Myatt’s linguistic decisions reveal an ethos of the Western pagan world grounded in balance, harmony, elegance, and rectitude, and that earlier translators—particularly Ficino and the modern academic tradition—either suppressed or neutralised it.²³ For the authors of the articles appearing in Western Paganism, the Hermetica articulate a coherent civilizational disposition distinct from both Christian and secular modern values, and Myatt’s translation restores this dispositional structure to view.²⁴ From an etic perspective, however, such claims function less as historical reconstructions of Hermetic thought than as hermeneutic projections, selectively privileging certain elements of the late-antique vocabulary while downplaying the demonstrable syncretism and intercultural hybridity emphasised in modern scholarship. It is within this tension—between linguistic reconstruction and ideological projection—that Myatt’s translation must be situated.

Semantic Reconfigurations in Myatt’s Translation

A. φῶς (phos) and the Rhetoric of Archaic Presence

Myatt’s decision to retain φῶς (phos) in transliteration rather than translate it as “light” constitutes one of the most conspicuous departures from established translation practice and offers a useful entry point into his broader semantic program. In the Greek text of Poemandres, the narrator describes being overwhelmed by phos immediately before the revelatory figure identifies itself as νοῦς.²⁵ Ficino renders phos as lux, embedding the scene within the Christianized Neoplatonic discourse of divine illumination, wherein light symbolises both intellectual clarity and spiritual ascent.²⁶ Modern translations—Copenhaver’s in particular—follow suit by opting for the unmarked English “light,” treating the term as a neutral descriptor of perceptual intensity.²⁷ Yet neither choice adequately reflects the term’s wider semantic range in archaic and classical Greek. In Homer, phos can denote the radiance of life or vitality (phos aēō) as much as visual illumination; in the mystery cults, light often signifies the presence of a deity or theophanic rupture rather than a metaphor for cognition.²⁸ By leaving phos untranslated, Myatt implicitly invokes these older registers, resisting the assimilation of Hermetic imagery to Christian symbolism and instead foregrounding the term’s polyvalent, pre-Christian potential. Stirling underscores this point by noting that Myatt’s retention of terms such as phos forms part of “a technical vocabulary… transporting the reader to an ancient world,” one that, in her view, “breath[es] new life into the texts and thence into Hermeticism itself.”²⁹ Whether this reconstruction reflects the intentions of the Hermetic authors is another matter; what is clear is that Myatt uses transliteration as a rhetorical strategy to estrange the reader from familiar interpretive pathways and to produce an atmosphere of archaic immediacy. This choice, while philologically permissible, functions primarily as a hermeneutic signal, announcing that the text is not to be read through late-antique Christian or modern rationalist categories but through a reconstructed “pagan” conceptual horizon.

B. νοῦς (nous) and Myatt’s Neologism “Perceiveration”

The Hermetic conception of νοῦς (nous) presents one of the most difficult interpretive challenges for translators, given the term’s extensive philosophical genealogy prior to its appearance in the Corpus Hermeticum. In Poemandres, the revelatory being identifies itself unambiguously as Nous, declaring: “ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ νοῦς, ὁ νoῦς ὁ ἀγαθός· παραγίγνομαι τοῖς ἁγίοις καὶ ἀγαθοῖς καὶ καθαροῖς καὶ ἐλεήμοσιν.”³⁰ Ficino renders this as mens bona—“the good mind”—in keeping with his Christian-Neoplatonic commitment to identifying nous with the divine intellect accessible to the purified soul.³¹ Plato (427–347 BCE) had earlier defined nous as the faculty by which the mind apprehends the Forms, the highest dimension of cognitive life, while Plotinus (204/5–270 CE) elevated Nous into a hypostasis of the intelligible realm, a radiant sphere of self-thinking thought.³² Even Copenhaver, whose 1992 translation aims for philosophical neutrality, maintains “Mind” as the default rendering, implicitly situating the Hermetic text within the continuum of Hellenistic philosophical anthropology.³³ These choices reflect the dominant assumption that nous pertains primarily to rationality, intellectual clarity, or divine cognition. Myatt’s neologism “perceiveration” represents an intentional rupture with this tradition. By rejecting “mind,” “intellect,” and even “awareness,” he seeks to evoke what he describes as a pre-rational capacity for direct, immersive, and non-discursive apprehension—a form of perception not yet conditioned by later metaphysical systems.³⁴ Stirling expands this claim further, arguing that Myatt’s “perceiveration” restores a mode of cognition characteristic of the pagan worldview—one marked not by abstract intellection but by the continuous presence of the numinous in all acts of seeing.³⁵ The difficulty, however, lies in the fact that modern scholarship on the Hermetica emphasises the conceptual eclecticism of their use of nous. Fowden’s analysis highlights its oscillation between Middle Platonic, Stoic, and Egyptian theological registers. At the same time, van den Broek stresses that the Hermetic nous functions as both a cosmic intellect and an internal principle of spiritual transformation, depending on the tractate.³⁶ Myatt’s attempt to impose an archaic, unified semantic field onto nous—however rhetorically effective—therefore represents a selective reconfiguration rather than a recovery of an original doctrinal core. The resulting term, “perceiveration,” operates less as a philological solution than as a hermeneutic tool that reorients the reader toward a reconstructed pre-Christian cognitive horizon.

C. λόγος (logos) and the Construction of a Ritual Vocabulary

Myatt’s rendering of λόγος (logos) as “numinous logos” further illustrates his effort to construct a semantic field that resists the dominant philosophical and theological appropriations of the term. In classical and Hellenistic usage, logos encompasses a broad range of meanings: reasoned discourse, rational principle, account, measure, or the structuring order of the cosmos.³⁷ The Stoics famously elevated logos to the status of an immanent divine rationality permeating all things, while early Christian texts—in particular the Johannine prologue, “Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος” (“In the beginning was the Word”)—recast logos as the pre-existent Christ, thereby infusing the term with a metaphysical and redemptive dimension that would shape its subsequent reception for centuries.³⁸ Within the Corpus Hermeticum, logos appears in several distinct registers. In Poemandres, it emerges as a creative principle through which nous articulates the structure of the cosmos; in Hermeticum XII, the logos serves as the medium by which knowledge of the divine is communicated to the initiate; and in the technical Hermetic fragments, logos shades into ritual utterance, approaching the “barbarous names” of the Greek Magical Papyri.³⁹ Modern translators typically stabilise this variety by rendering logos simply as “Word” or “Reason,” thereby aligning Hermetic usage with familiar philosophical or theological categories.⁴⁰ Myatt rejects this stabilising impulse by adding the qualifier “numinous,” a term he uses throughout his work to denote experiential, pre-discursive contact with sacred presence.⁴¹ Stirling interprets this choice as evidence of a “ritual ontology” underlying the Hermetica, arguing that Myatt’s “numinous logos” restores a pre-Christian understanding in which logos denotes “the sacred utterance that participates in the ordering of the cosmos,” rather than the Christianized notion of the divine Word or the Stoic rational principle.⁴² Yet modern scholarship presents a more complex picture. Fowden emphasises that the Hermetic logos oscillates between philosophical discourse and revelatory speech, reflecting the hybrid environment of Roman Egypt in which philosophical instruction, temple theology, and magical praxis intersected.⁴³ Copenhaver similarly notes that the logos in the Hermetica cannot be extricated from its late-antique blending of Platonic metaphysics with Egyptian notions of speech as creative potency.⁴⁴ Myatt’s “numinous logos,” by privileging a unified ritual sense of the term, thus imposes a coherence not readily supported by the heterogeneous textual evidence. As with “perceiveration,” the effect is not philological clarification but a reorientation of the reader’s interpretive horizon, redirecting attention from philosophical abstraction to a reconstructed sacred vocabulary associated with a putative Western pagan worldview.

D. Synthesis: Semantic Isolation and the Construction of a Pagan Conceptual Field

Considered together, Myatt’s renderings of φῶς (phos), νοῦς (nous), and λόγος (logos) produce not merely isolated lexical innovations but a coherent semantic system that deliberately detaches the Hermetic vocabulary from its historically attested zones of interaction—Platonic metaphysics, Stoic cosmology, Jewish exegetical traditions, Egyptian temple theology, and early Christian speculation. His transliteration of phos situates the visionary experience outside the moral and epistemic connotations associated with “light” in Christian and Neoplatonic discourse. His neologism “perceiveration” removes nous from the long history of intellectualist or contemplative readings, reframing it as an experiential, pre-discursive, and quasi-instinctual modality. And his “numinous logos” repositions logos within a ritual or theurgic register, emphasising sacred utterance rather than philosophical rationality or Christological identity.⁴⁵ In effect, Myatt constructs what might be termed a semantic enclave: a zone of meaning insulated from the dominant interpretive trajectories that have shaped Hermetic reception since the Renaissance. Stirling and other authors interpret this enclave as the re-emergence of an underlying Western pagan ethos, claiming that Myatt’s vocabulary reveals the conceptual structure of a primordial worldview that later traditions sought to suppress or domesticate.⁴⁶ Yet the very coherence of this reconstructed field raises questions, given the documented heterogeneity of the Hermetic materials. As van den Broek and Mahé have shown, the Hermetica do not articulate a unified system but reflect the pluralistic religious and intellectual environment of Roman Egypt, where Greek philosophical terms, Egyptian theological motifs, and ritual technologies intermingle without synthesis.⁴⁷ Myatt’s translation, by contrast, imposes a systematic conceptual unity, one that accentuates certain archaic or pagan resonances while minimising the syncretic interactions evident in the primary sources. The result is a lexicon that functions not as an index of late-antique hybridity but as a programmatic articulation of a reconstructed pagan cosmology, prepared for further ideological elaboration.

Western Paganism’s Interpretive Framework: Reconstructing a Western Pagan Ethos

A. Rachael Stirling’s collection as Interpretive Intervention

Stirling’s collection of articles on Western paganism and Hermeticism, although written outside formal academic channels, is best approached as a deliberate and fully articulated interpretive intervention within the contemporary reception of the Corpus Hermeticum and therefore warrants careful analytical consideration. The authors present Myatt’s translation not simply as a stylistic alternative to academic versions but as critical evidence for a larger historical thesis: that the Hermetica articulate a coherent and continuous Western pagan ethos effaced by Christianisation and obscured by modern scholarship. The authors’ argument proceeds from the assumption that the conceptual field reconstructed through Myatt’s lexical interventions—phos, “perceiveration,” “numinous logos”—is not an interpretive creation but a revelatory disclosure of the Hermetica’s original worldview. As Western Paganism argues, the pagan ethos of the Greek and Roman world—an ethos of balance, harmony, elegance, rectitude—was supplanted by Christianity. Myatt’s translation, therefore, restores this ethos to the Hermetic writings, revealing what earlier Christian translators obscured.⁴⁸ This framing aligns with what Kocku von Stuckrad describes as the genealogical mode of Western esotericism, wherein ancient texts are mobilised to articulate narratives of cultural origin, continuity, and loss.⁴⁹ Rather than situating the Hermetica within the syncretic, pluriform intellectual environment documented by historians of late antiquity, Western Paganism posits a unified civilizational substratum, a pagan conceptual coherence that precedes and transcends the demonstrable heterogeneity of the sources. From an etic standpoint, such a reading is analytically significant not because it recovers a suppressed historical worldview, but because it illuminates how modern interpreters mobilise ancient esoteric texts to construct contemporary identities and frameworks of cultural meaning.

B. Constructing “Pagan Ethos” Through Philology

Central to Stirling’s interpretive framework is the assertion that the Hermetica encode a distinctive Western pagan ethos characterised by balance, harmony, elegance, rectitude, a conceptual disposition she regards as continuous across Greek and Roman religious life and allegedly recoverable through Myatt’s translation.⁵⁰ This ethos is not defined by specific doctrinal content but by a style of apprehending the world—one rooted, in her view, in an immediate and embodied encounter with the “numinous” that predates the intellectualisation she attributes to Christianity and later philosophical systems. To substantiate this claim, the authors of Western Paganism selectively foreground elements of Myatt’s vocabulary that emphasise pre-rational or pre-discursive perception. Thus, Myatt’s “perceiveration” becomes evidence of a pagan cognitive modality grounded in intuitive presence rather than reflective thought; his retention of phos becomes proof of an archaic sensibility in which “light” signifies energetic or ontic presence rather than moral illumination; and his “numinous logos” is interpreted as a recovery of a ritualised understanding of speech as cosmically efficacious.⁵¹ What remains absent in this construction is the considerable diversity of semantic and ritual registers in the primary sources themselves. The Hermetica do contain passages that resonate with this particular emphasis on presence and embodied perception—for example, the depiction of the soul’s encounter with the seven rulers in Poemandres, or the invocation of sacred utterances in the technical Hermetica—but these coexist with passages that reflect Middle Platonic metaphysics, Stoic cosmology, Egyptian theological structures, and Jewish exegetical motifs.⁵² Stirling et al.’s interpretive strategy thus involves elevating certain components of the textual tradition while bracketing or downplaying others, producing a unified ideological construct that contrasts with the text’s documented plurality. From an analytical perspective, this selectivity does not invalidate her interpretive project; rather, it highlights how Myatt’s translation functions as a hermeneutic catalyst, enabling the articulation of a cohesive pagan framework where the original materials present a far more heterogeneous picture.

C. Modern Scholarship and the Problem of Hermetic Unity

When juxtaposed with the conclusions of modern Hermetic scholarship, Western Paganism’s assertion of a unified Western pagan ethos encounters substantial historiographical complexity. Garth Fowden’s The Egyptian Hermes—still the most influential synthetic study of the Hermetica—argues that the texts emerged from the “religious and intellectual pluralism” of Roman Egypt, where Greek philosophical discourse, Egyptian temple theology, and foreign ritual technologies intermingled in a structurally hybrid environment.⁵³ Roelof van den Broek similarly emphasizes that the Hermetica exhibit neither doctrinal coherence nor a singular cultural lineage; instead, they present a “fluid and heterogeneous body of revelation literature” in which distinct voices and traditions coexist.⁵⁴ Jean-Pierre Mahé’s philological work reinforces this point, showing that the Hermetic conceptual vocabulary shifts significantly across tractates, reflecting varying degrees of Hellenistic philosophical influence and Egyptian theological imagery.⁵⁵ Even Copenhaver’s critical edition—despite its aim of producing conceptual consistency—acknowledges the “multivocality” of the sources and the impossibility of reducing them to a stable philosophical system.⁵⁶ Against this backdrop, the ONA’s reading appears less as a recovery of a suppressed historical substratum than as an interpretive consolidation, one that extracts from the texts those elements that resonate with her reconstruction of a pagan ethos while omitting the heterogeneous elements documented in the primary materials. The importance of this divergence is not evaluative but analytical: it highlights the extent to which Myatt’s translation invites—and perhaps intentionally enables—such consolidations. By creating a consistent semantic field rooted in archaic resonance, Myatt provides a conceptual infrastructure that supports Western Paganism’s unilinear historical narrative, even as modern scholarship underscores the fundamentally syncretic character of the Hermetic tradition.

Translation, Reception, and the Construction of Hermetic Identity

The contrast between Myatt and Stirling’s reconstruction of a coherent pagan conceptual world and the pluriformity emphasised by modern scholarship raises a broader question about how Hermetic identity itself is produced through translation and reception. The Corpus Hermeticum has never existed as a self-contained doctrinal system; rather, it has served as a receptive substrate, continually reshaped by the interpretive frameworks of those who translate, comment upon, or appropriate it. Ficino framed Hermes as a proto-Christian sage, Mead as a perennialist mystic, and Copenhaver as a late-antique philosophical writer.⁵⁷ Myatt, Stirling, and the other contributors to Western Paganism represent another moment in this genealogy, articulating a thoughtful and internally coherent reading in which Hermes becomes the voice of an archaic Western pagan ethos. The significance of this move lies less in its historical claims than in its demonstration of how ancient esoteric texts function as sites of conceptual projection, enabling modern interpreters to articulate narratives of identity, continuity, rupture, or recovery. The Hermetica’s inherent conceptual flexibilities—its alternation between philosophical dialogue, revelatory discourse, cosmology, ritual instruction, and soteriology—facilitate these projections by providing a textual field sufficiently indeterminate to sustain divergent interpretive systems.⁵⁸ Myatt’s translation, by generating a tightly bound semantic enclave, effectively proposes a new possible identity for Hermetic philosophy, one that stands in deliberate contrast to the Christian, Neoplatonic, and academic models that have dominated the tradition since the Renaissance.

Understanding Myatt’s translation as an act of conceptual creation rather than mere linguistic substitution aligns with broader insights from reception theory, which emphasises that texts acquire meaning through historically situated acts of interpretation rather than through the recovery of an immutable original. Hans-Georg Gadamer’s model of wirkungsgeschichtliches Bewusstsein—“historically effected consciousness”—underscores that interpreters inevitably approach ancient texts through the horizon of their own cultural presuppositions and existential concerns; this horizon does not distort understanding so much as constitute its very possibility.⁵⁹ Scholars of Western esotericism, including Antoine Faivre and Wouter Hanegraaff, have extended this insight further by arguing that esoteric traditions are often defined not by stable doctrinal content but by modes of organizing and recontextualizing inherited materials.⁶⁰ In this sense, Myatt’s translation stands as a paradigmatic example of esoteric reception: it does not merely transmit the Hermetica but actively reconfigures them to articulate a distinct metaphysical and cultural vision. Stirling’s collection of articles—well researched, philosophically engaged, and methodologically consistent within their own framework—demonstrates how such reconfigurations can rapidly become embedded within broader ideological narratives, illustrating how translation can catalyse new forms of traditionalism, identity construction, or counter-historical genealogy.⁶¹ From an etic perspective, the significance of Myatt’s translation therefore lies less in the accuracy of its claims about late antiquity than in its capacity to generate a new Hermetic identity, one whose coherence derives from modern interpretive needs rather than historical uniformity. This dynamic situates Myatt within a long continuum of figures—from Ficino to Mead—who have engaged the Hermetica not simply as historical artefacts but as productive resources for the ongoing reimagining of Western esoteric thought.

Seen within the broader landscape of contemporary post-secular culture, Myatt’s translation—and Stirling’s corresponding interpretation—participate in a wider set of identity-forming projects that mobilise antiquity as a resource for reimagining the present. Scholars such as Aleida Assmann and Jan Assmann have emphasised that cultural memory operates through processes of selective retrieval and reinvention, whereby the past is continually reshaped to meet the symbolic needs of specific communities.⁶² Myatt’s reconstruction of an archaic pagan lexicon thus functions not exclusively as a philological enterprise but as a contribution to what the Assmanns term a “normative past,” a curated representation of antiquity that offers models of ethical orientation, cosmology, and belonging. Stirling et al.’s narrative of a suppressed Western pagan ethos engages this dynamic in a sophisticated way, embedding Myatt’s vocabulary within a counter-historical genealogy that posits continuity where historical evidence indicates diversity, and displacement where scholarship documents complex cultural interchange.⁶³ This is not unique to their work; it reflects a broader tendency within contemporary Western esotericism and neo-pagan movements to articulate identities through appeals to symbolically charged models of the past.⁶⁴ In this context, the Hermetica serve as particularly fertile ground for such projects, precisely because their textual multivalence allows them to be appropriated in multiple, often incompatible ways. Myatt’s translation crystallises one such possibility, offering a lexically unified and conceptually coherent representation of Hermetic thought that contrasts sharply with the historically attested heterogeneity of the tradition. His work thus exemplifies how translation, far from being a peripheral scholarly activity, can function as a primary site of cultural production—shaping not only how ancient texts are read, but also how they are woven into the identities and imaginaries of the present.

Notes

David Myatt, Poemandres: A Translation (self-pub., 2013).

Corpus Hermeticum I, in A.D. Nock and A.-J. Festugière, Corpus Hermeticum, 4 vols. (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1945–54).

Myatt, Poemandres: A Translation, opening vision section.

Rachael Stirling, Western Paganism and Hermeticism: Myatt and the Renaissance of Western Culture (Ragnarok Publications, 2020).

Marsilio Ficino, Hermetis Trismegisti Pimander, in Opera Omnia (Basel, 1576).

See A.D. Nock and A.-J. Festugière, Corpus Hermeticum; Brian P. Copenhaver, Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

Myatt, Poemandres: A Translation, introduction.

Stirling, Western Paganism and Hermeticism.

Ibid.

Garth Fowden, The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993); Roelof van den Broek and Jean-Pierre Mahé, eds., Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times (Albany: SUNY Press, 1998).

Plato, Republic VI–VII; Phaedo, passim.

Numenius of Apamea, fragments in E. des Places, Numénius, Fragments (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1973).

Gospel of John 1:1–18; various Pauline epistles.

On the manuscript tradition and internal diversity, see Nock and Festugière, Corpus Hermeticum, vol. 1, introduction.

Nock and Festugière, Corpus Hermeticum, esp. vol. 1, xix–xliv.

Ficino, Hermetis Trismegisti Pimander; see also Paul Oskar Kristeller, The Philosophy of Marsilio Ficino (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1943).

On Ficino and Prisca Theologia, see Kristeller, Philosophy of Marsilio Ficino, and D.P. Walker, The Ancient Theology (London: Duckworth, 1972).

G.R.S. Mead, Thrice-Greatest Hermes, 3 vols. (London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1906).

Copenhaver, Hermetica.

Van den Broek and Mahé, Gnosis and Hermeticism, esp. introduction.

Myatt, Poemandres: A Translation, introduction.

Cf. Myatt’s broader discussions of nous and experience in his Hermetic essays (self-published).

Stirling, Western Paganism and Hermeticism.

Ibid.

Corpus Hermeticum I, 1–4, in Nock and Festugière, Corpus Hermeticum.

Ficino, Hermetis Trismegisti Pimander.

Copenhaver, Hermetica; Mead, Thrice-Greatest Hermes.

E.g., Homer, Iliad and Odyssey; on phos and mystery imagery, see Walter Burkert, Ancient Mystery Cults (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987).

Stirling, Western Paganism and Hermeticism.

Corpus Hermeticum I.19 (Greek text in Nock–Festugière).

Ficino, Hermetis Trismegisti Pimander ad loc.

Plato, Republic VI–VII; Plotinus, Enneads V.1, V.3, V.9.

Copenhaver, Hermetica, ad loc.

Myatt, Poemandres: A Translation, introduction and translator’s notes.

Stirling, Western Paganism and Hermeticism.

Fowden, Egyptian Hermes; van den Broek and Mahé, Gnosis and Hermeticism.

See standard lexica; for a concise overview, see G.E.R. Lloyd, Polarity and Analogy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966).

On Stoic logos, see A.A. Long and D.N. Sedley, The Hellenistic Philosophers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987); on John 1, see Raymond E. Brown, The Gospel According to John (New York: Doubleday, 1966).

Corpus Hermeticum I, XII; and the Greek Magical Papyri (PGM).

Ficino, Mead, and Copenhaver, passim.

Myatt, Poemandres: A Translation, introduction.

Stirling, Western Paganism and Hermeticism.

Fowden, Egyptian Hermes, esp. chs. 2–3.

Copenhaver, Hermetica, introduction and notes.

For a synthetic view of these fields, see Fowden, Egyptian Hermes.

Stirling, Western Paganism and Hermeticism.

Van den Broek and Mahé, Gnosis and Hermeticism; Mahé, Hermès en Haute-Égypte, 2 vols. (Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 1978–82).

Stirling, Western Paganism and Hermeticism.

Kocku von Stuckrad, Locations of Knowledge in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Esoteric Discourse and Western Identities (Leiden: Brill, 2010).

Stirling, Western Paganism and Hermeticism.

Ibid.

On the diversity of themes in the Hermetica, see Fowden, Egyptian Hermes, and Copenhaver, Hermetica, introduction.

Fowden, Egyptian Hermes, 1–10.

Van den Broek, in van den Broek and Mahé, Gnosis and Hermeticism.

Mahé, Hermès en Haute-Égypte.

Copenhaver, Hermetica, introduction.

On Ficino, Mead, and Copenhaver as moments in reception, see Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Fowden, Egyptian Hermes; van den Broek and Mahé, Gnosis and Hermeticism.

Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, 2nd rev. ed., trans. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall (New York: Continuum, 1994).

Antoine Faivre, Access to Western Esotericism (Albany: SUNY Press, 1994); Hanegraaff, Esotericism and the Academy.

Stirling, Western Paganism and Hermeticism.

Aleida Assmann, Cultural Memory and Western Civilisation: Functions, Media, Archives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Jan Assmann, Religion and Cultural Memory (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006).

Aleida and Jan Assmann, works cited above.

On contemporary Western esotericism and neo-paganism, see Egil Asprem and Kennet Granholm, eds., Contemporary Esotericism (Sheffield: Equinox, 2013).

Bibliography

Assmann, Aleida. Cultural Memory and Western Civilisation: Functions, Media, Archives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Assmann, Jan. Religion and Cultural Memory. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006.

Asprem, Egil, and Kennet Granholm, eds. Contemporary Esotericism. Sheffield: Equinox, 2013.

Brown, Raymond E. The Gospel According to John. New York: Doubleday, 1966.

Copenhaver, Brian P. Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Ficino, Marsilio. Hermetis Trismegisti Pimander. In Opera Omnia. Basel, 1576.

Faivre, Antoine. Access to Western Esotericism. Albany: SUNY Press, 1994.

Fowden, Garth. The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Truth and Method. 2nd rev. ed. Translated by Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall. New York: Continuum, 1994.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J. Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Kristeller, Paul Oskar. The Philosophy of Marsilio Ficino. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1943.

Long, A.A., and D.N. Sedley. The Hellenistic Philosophers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Mahé, Jean-Pierre. Hermès en Haute-Égypte. 2 vols. Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 1978–82.

Mead, G.R.S. Thrice-Greatest Hermes. 3 vols. London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1906.

Myatt, David. Poemandres: A Translation. Self-published, n.d.

Nock, A.D., and A.-J. Festugière. Corpus Hermeticum. 4 vols. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1945–54.

Numenius. Numénius, Fragments. Edited by E. des Places. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1973.

Plato. Republic. Phaedo. Various standard editions.

Plotinus. The Enneads. Various standard editions.

ed. Stirling, Rachael. Western Paganism and Hermeticism: Myatt and the Renaissance of Western Culture. Ragnarok Publications, 2020.

van den Broek, Roelof, and Jean-Pierre Mahé, eds. Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times. Albany: SUNY Press, 1998.

von Stuckrad, Kocku. Locations of Knowledge in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Esoteric Discourse and Western Identities. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Walker, D.P. The Ancient Theology: Studies in Christian Platonism from the Fifteenth to the Eighteenth Century. London: Duckworth, 1972.

Burkert, Walter. Ancient Mystery Cults. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Lloyd, G.E.R. Polarity and Analogy: Two Types of Argumentation in Early Greek Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966.

Thank you. An excellent and needed overview re the interpretation of an ancient text important to both understanding an alternative modern (pagan) 'world-view' and the Occult movement you're investigating. For those few interested, Myatt's translation and commentary is included in "Corpus Hermeticum: Eight Tractates" available (a) since 2017 in printed form: ISBN-13 978-1976452369 and (b) as a free pdf at https://archive.org/download/eight-tractates-v2-print/eight-tractates-v2-print.pdf

Hello there Chris, I hope you are well friend.

I’ve been seeing your notes for a while now, always thought provoking, thank you.

I thought you may enjoy what I talk about, I take a different approach to history, focusing on obscure historic books.

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/15th-century-alchemical-healing